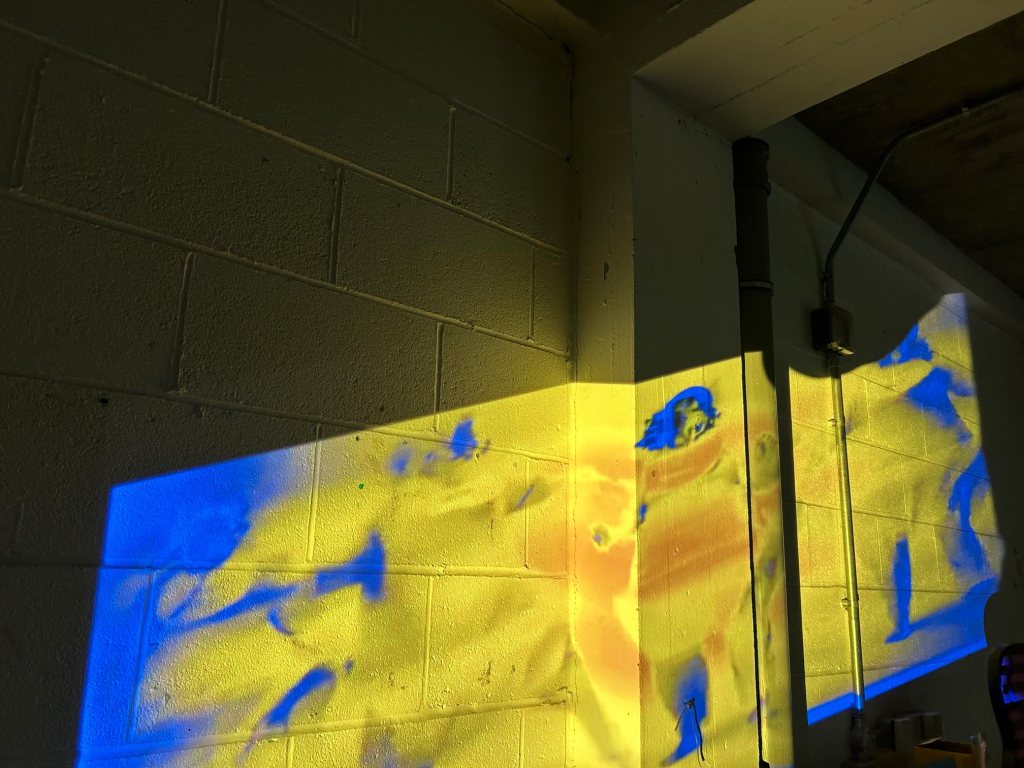

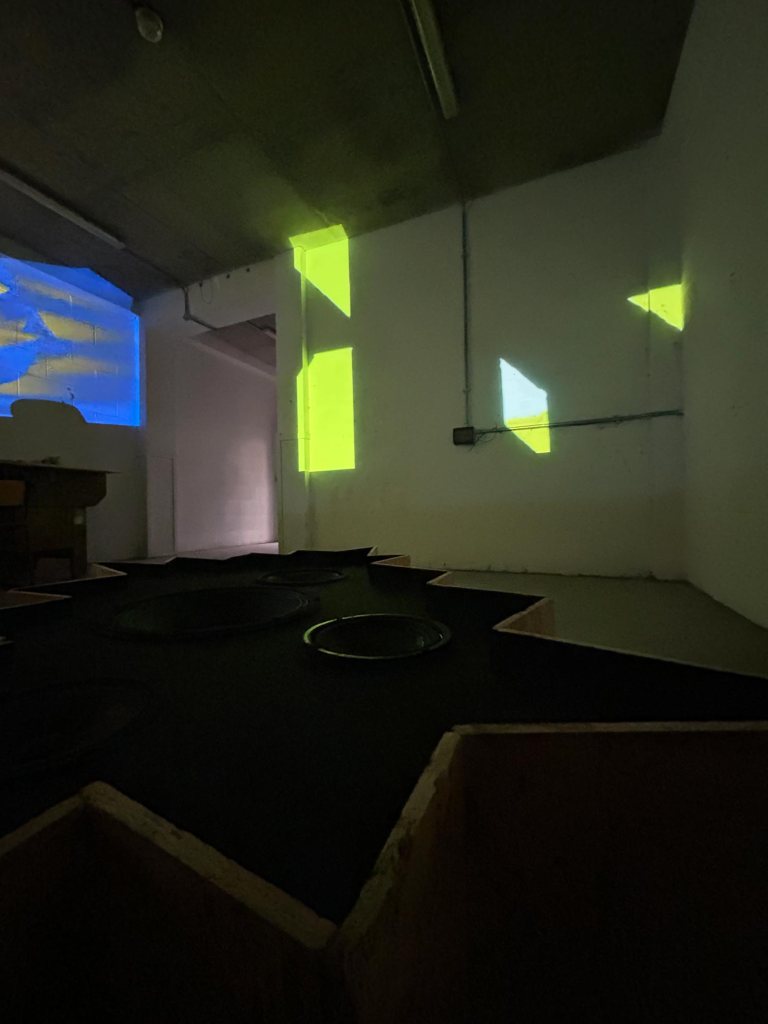

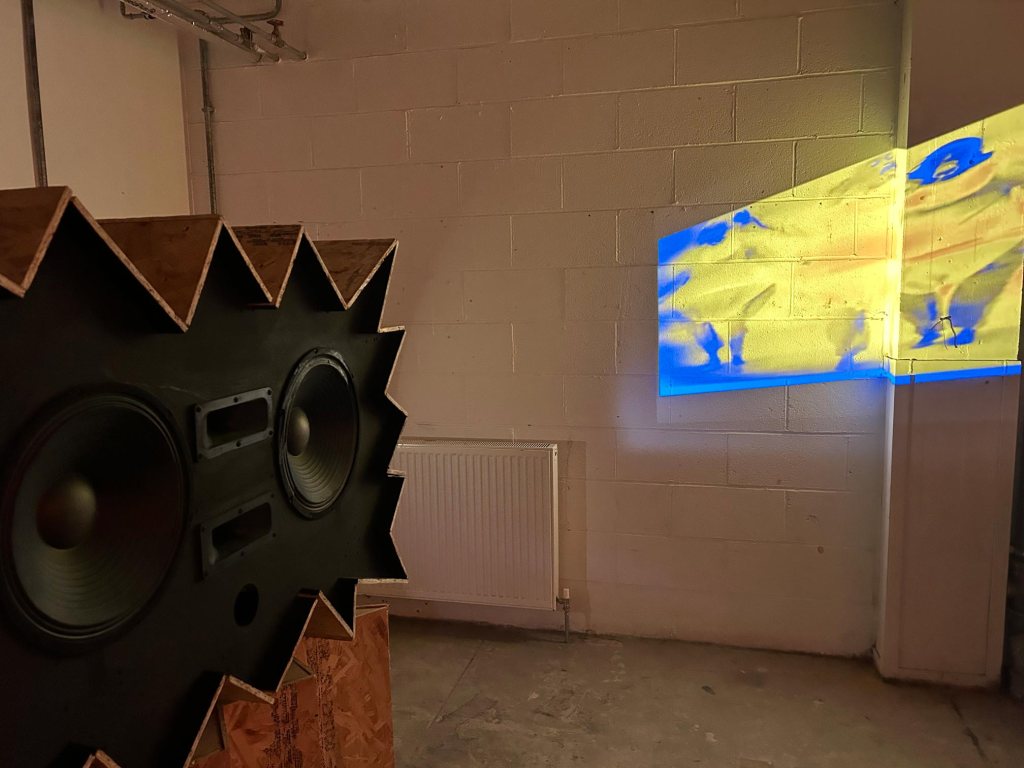

Please Sir Can I Have Some More Bass? enjoyed a second outing on March 22nd at the Whisky Bond, Glasgow. Jamie’s sound system had double speakers and double the power. The sound was overwhelming! My video was spliced from the first Please Sir with more archive footage from the old 1990s and early 2000s VJ clips hidden in a recently found hard drive – a couple of these old clips were made by past pals Scott Smyth and Nick & Dan Roy, and it was really great to reflect on those times through the lens of the clips.

This reflection made me turn once again to this ephemeral field of media archeology that I briefly explored in the first Please Sir. I though I might write a little about what it is firstly. Then I thought I might use that lens to talk a little about the DIY dance music culture. Next I’ll discuss the visual VJ component, finally tying it in to a short discussion of the rejection of the scene by the art world.

Media archeology is a field of inquiry first pursed by academics and film theorists in the early 2010s. It’s definition can be problematic, but in my last Please Sir post I explored the idea of recollecting past techniques and technologies of production. If we consider Marshall McLuhan’s treatise that the ‘medium is the message’, we might view these technologies as signifying the advent or beginning of user generated content, or what has become known as Web 2.0. McLuhan thought the medium of any content could be viewed as more important than the content itself. This is a useful definition for media archeology, but Erkki Huhtamo goes further to claim it provides an opportunity to create dialogues between the present and different moments in the past.

But is this definition really at the heart of the Please Sir experiments? Or was Please Sir instead an action of ‘doing now’, rather than ‘reflecting on then’? As Dr Jussi Prikka claims in his recent reflection,

‘the field and its methods were at least partly invented by artists who through installations, sound and audiovisual works, as well as process-based methods had investigated what it meant to turn to seemingly obsolete media in the midst of burgeoning “newness” of internet and digital culture’ (Prikka, 2023)

With this idea in mind, Please Sir can be viewed as inherently post-modern, which of course media archeology must be, and a chance to create a new, amalgamated real-world experience from the collision of historical and current analogue and digital media.

Therefore, ‘media archeology is a multi layered construct’ according to Huhtamo. Please Sir involved VJ clips, a sound system made from Jamie’s large bass bins, music that recollected Acid, Techno and Rave culture of the 1980s and 90s. Please Sir was shown in a concrete-bunker-like exhibition space – a miniature version of the reclaimed industrial spaces of the DIY techno-culture scene of the 90s (not forgetting the the Whisky Bond is a reclaimed industrial space itself). By interogating these multiple layers of technology and space, Please Sir also explored the myths and truths that made up that culture: what was it like to view this media or listen to that music? Who made these media artifacts and why? And most importantly, how was this DIY movement and its patronage reflective of a broader culture? I’ll now attempt to answer these questions.

The culture Please Sir reflects upon is the Rave scene of the late 1980s and 90s. As a side note, I don’t like this word Rave – it trivialises a complex set of interconnected conceptual subcultures, sounds and presentations – but for simplicity we’ll stick with it. The Rave scene was inhabited by children born largely in the 1970s, sometimes called Generation X. Rave culture was thought to be a puerile affair at the time: a pursuit of the young and hedonistic. What’s forgotten though is that Gen X evolved from latch-key living where their childhood past-times were made up by, and centered on, themselves. This is because these kids were the first generation where both parents worked, and were left largely in charge of their own care. It stands to reason that their young adult culture would be one borne from a DIY principle. And don’t forget that the music, fashion and art that immediately preceded them, the culture of their big brothers and sisters, was Punk! This movement collaged and montaged ideas from elsewhere, stitching guitar riffs from rock, and creating images and fashion from stolen newsprint, safety pins and recycled fabrics!

Punk, and then Acid and Rave recoiled from the Thatcher years; from the bankruptcy of opportunities. Thatcher’s infamous speech, ‘There is no such thing as society’ (which I have sampled here) exemplified the alienation Gen X experienced growing up. With few jobs to graduate to from high school as industrial decline and traditional employment evaporated, with religion in decline, organised communities ransacked by right wing Tory politics, young people, like their punk siblings, turned to music for their community. Where ideological Thatcherism celebrated and elevated individualism, Rave culture ‘expressed deeply-felt desires for communal experience which Thatcher rejected’ (Collin, 2009).

In a world of few jobs or opportunities, young people (and I love the irony here) turned to the state for subsistence. State benefits like Job Seekers Allowance, Income Support and Housing Benefit demanded that claimants turn up to local job centers every two weeks to sign-on – that is, declare themselves fit and able to work. But with very few jobs to apply for, and those that were available, paid disastrously low wages, especially for city dwellers, some young people filled their time with creative pursuits. Artists and musicians used the time on their hands to produce some of the most ground breaking media, arguably unmatched since. As the first generation to grow up with home computers (ZX Spectrums and Commodore or Armstrad computers were not unknown in lower middle class families, and high schools often housed BBC micro-computers throughout the early eighties), Gen X kids were quick to use their unemployed free time exploiting pirated software to produce art, video and audio for DIY or ‘underground’ raves.

Lev Manovich, In his 2002 essays on New Models of Authorship detailed some of the ways computers facilitated new DIY content. For example, he argues that remixing and sampling, central pillars to the rave sound, originally had a precise and a narrow meaning that gradually became diffused. It was the introduction of multi-track digital mixers that made remixing a standard practice. With each element of an audio track – bass, drums, etc. – available for separate manipulation, it became possible to ‘re-mix’ the song: change the volume of some tracks or substitute new tracks for the old ones.

Now it would be crazy for me to argue that disaffected young British kids were responsible for the global turn to dance music. In his DJ Culture Ulf Poscardt singles out different stages in the evolution of remixing practice and in turn dance music in general (1998). In 1972 DJ Tom Moulton mixed his first disco remixes using 2 turntables which would become the staple instrument for House, Acid, Techno and Electro club nights (Electro would later become Hip-Hop). By 1987, ‘DIY DJs started to ask other DJs for remixes’ and the treatment of the original material became much more aggressive. To this were added techno sounds, often from Roland’s 101, 303, and 808 drum machines, sequencers and samplers creating an electronic sound unheard of before. This development, particularly popular in Chicago and Detroit contributed massively to the burgeoning UK rave scene that exploded with the Second Summer of Love and Acid House music in 1988.

Acid house music, characterized by its repetitive beats and synthesized basslines, became the soundtrack of the Second Summer of Love. Young people, empowered by the DIY spirit, began organising illegal raves in warehouses, fields, and in Glasgow railway tunnels were popular. We even went to a Rave in a carriage pulled by a steam train in Bo’ness. Later I helped organise a party on a boat that sailed around Loch Lomond! These events were a direct challenge to the established nightlife industry, which was often seen as restrictive and expensive. Rave organisers, often operating outside of the law, would use word of mouth, flyers, and pirate radio stations to spread information about upcoming events. This underground network was crucial in fostering a sense of community and rebellion, as participants felt they were part of something distinct from mainstream society.

Furthermore, DIY culture played a role in the distribution of music associated with the the burgeoning Rave scene. Independent record labels sprang up to release acid house tracks that mainstream labels were hesitant to touch. These labels, often run out of bedrooms and small offices, were instrumental in circulating the new sound. White label records – vinyl pressings without any identifying labels – became a popular medium, allowing DJs to share and play new tracks without the influence of major record companies. This created a sense of exclusivity and underground credibility.

The DIY approach also extended to the visual aesthetics of the Second Summer of Love. The iconic smiley face, a symbol of the movement, was a simple, easily reproducible image that was plastered on t-shirts, posters, and flyers. This accessible visual style was emblematic of the broader DIY mentality: it didn’t require a professional designer to create something impactful. The flyers, like Punk predecessors were often produced using photocopiers and simple graphic design tools, became a significant part of the culture, acting as both promotional material and art. Manovich argues that the introduction of electronic editing equipment such as switcher, keyer, digital storage and photo editing, democratised production and challenged established notions of authenticity. Remixing and sampling became a common practice in video production too towards the end of the 1980s and in to the 90s; first pioneered in music videos, it later took over visual culture resulting in a visual compliment to the DIY rave music of the era: VJing!

VJing, short for ‘Video Jockeying’, is the live manipulation and mixing of visual media, often synchronized with music, to create immersive audiovisual experiences. Originating in the 1980s and early 90s, VJing initially developed alongside the rise of DIY rave culture, where visuals were projected in club spaces to enhance the atmosphere. Just as DJs mix audio tracks, VJs mix video clips, animations, graphics, and effects in real-time, responding to the music and the crowd’s energy. Many VJs remixed pre-made content, as a DJ does, but the better VJs created their own unique content too. My memories are of recording clips I made on my computer on to VHS tapes and carting them along with a couple of VCRs and a switcher to a club. It evolved quickly as software became more sophisticated and hardware became more portable where a VJ typically used specialised software and hardware to mix and project visuals onto large screens or other surfaces.

DJing and VJing, an extension of Video art was the last democratic practice to be brought in from the cold to the fine art canon. When I was at art school, I studied the practice as part of a post graduate degree in Electronic Imaging at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art in Dundee. Then the practice was looked down upon, viewed as ‘eye-candy’ by the more pious artists of the time. It’s only now that Vjing is viewed as an important milestone in the history of art. As a surrogate of Video Art, VJing denied the art world’s power-seeking, which was selling the sign-value of the artwork, which relies on prestige and status. Like Video Art, VJing dematerialised art. It’s ephemoral display and largely digital production, and that the artists were often considered outsider, meant that the critic, and so the art world, rejected the practice as pure pop. Taylor writes that the use of a computer was ‘the kiss of death’ for many artists when approaching gallery directors, limiting dissemination and keeping the practice firmly in the club (2014: p.4). Part of this is the problem of authenticity which seems to be a perennial one in the art world. Despite a long history of cutting, pasting, sticking, and re/presenting readymades, the art world finds it difficult to come to terms with post-modern practices of remixing and sampling, as explored earlier with the help of Manovich.

The fear and suspicion of the DIY practitioner and their art and sampled music has resulted in an art history and discourse that rendered it largely ignored. Despite its eventual domination and its co-emergence with sound art, special effects, large scale performances and of course, video art, it was habitually overlooked, associated with the dead eye of kitsch. For many critics, all parts of Rave culture had an unhealthy reliance on hedonism, community and celebration, and was divorced from moral, social and cultural life; or what the dominant ideology of capitalism decreed.

To conclude, the rapid expansion of the digital world and the arguably global success dance music and all it’s cultural components were categorised: Pop. Video art, installation, and sound art all dematerialised the art object, and in their own way reflected the rejection of individualism, consumerism, and monied notions of success. These cultural realms all fed into interests in Rave, Acid House, and DIY culture. Through the lens of media archeology, these new conceptual paths, which incorporated multidisciplinary approaches by and for lay people, are only now being celebrated for the true value they offered. And that’s what Please Sir, is at least partly, about.

In essence, Please Sir is as much a celebration of music and hedonism as it is to the power of DIY culture. The Rave movement’s success in creating a vibrant, alternative cultural landscape was rooted in the anti-establishment DIY ethos that encouraged individuals to take control of production, distribution, and organisation. By bypassing traditional gatekeepers, the youth of the UK were able to carve out a space for themselves, fostering a spirit of creativity, independence, and resistance that defined this transformative period.

Leave a comment