Part 3: Reception and Marginalisation of Computer Art

The late 1960s and early 1970s were a period of extraordinary technical innovation. Yet, despite the forward-thinking integration of technology and artistic experimentation during this era, art history has offered little sustained engagement with the visual artists who pioneered the convergence of art and technology. While specialists and digital art scholars have preserved this history, it remained marginalised in mainstream discourse. As digital art curator Wolf Lieser commented, it was not until around the year 2000 that major institutional shows of early computer art began to emerge. Charlie Gere similarly noted that ‘computer and art couldn’t possibly be in the same sentence together. We thought it had no history.’[1]

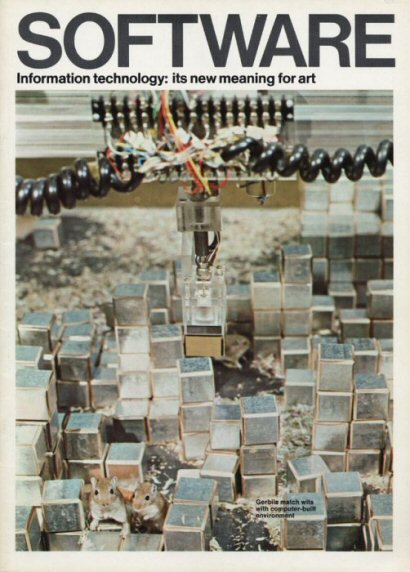

This post explores how the exhibitions Cybernetic Serendipity and Software were received within both mainstream media and the critical art world. It interrogates Burnham’s claim that ‘the art world has been consistently unanimous in its refusal to recognise or in any way support computer-based art,’[2] and examines why this form remained peripheral for decades. In doing so, it reveals how media, critical reception, institutional bias, and associations with militarism contributed to the exclusion of computer art from canonical discourse.

Media Reception: Popular vs Critical

The reception of Cybernetic Serendipity was largely positive in the popular press. Media reports highlighted its novelty and democratic appeal, noting how it attracted audiences unfamiliar with the art world. Newspapers including The Daily Mirror, The Guardian, Financial Times, The Sunday Telegraph, and The New Statesman reported on the show during its August 1968 run. Reviewers recognised that the exhibition challenged traditional notions of authorship: ‘That machines too can produce Art.’ Yet some critics, such as Michael Shepherd of The Sunday Telegraph, expressed dismay at what they perceived as a broader crisis in art. He wrote: ‘I don’t have the faintest idea these days what art is for or about.’[3] Another review noted the show’s ideological dimension, suggesting it could ‘combat the irrational fear many people have of machines and modern technology’ and might even ‘herald a revolution in the arts comparable to that caused by the computer in the realm of science.’[4]

In contrast, Software received a far more ambivalent response. A review in The New York Times described it as ‘confusing’ and fragmented, noting that ‘some works are jokey while other works are serious endeavours that escape the viewer.’ The term software was explained accurately as both programming and communication, but criticism centred on technical failures and corporate overtones. Some pieces were viewed as thinly veiled advertisements for commercial sponsors. Broken or inoperable works marred the visitor experience: ‘If Software were a better conceived show, its missing components might be more missed.’[5]

Technical Failures and Institutional Obstacles

Burnham argued that elements of Software were sabotaged.[6] Hans Haacke’s Visitors’ Profile initially failed due to a software fault in the DEC PDP-9 computer loaned by the Jewish Museum. An installation of five video loops showing artists at work was reportedly destroyed in a dispute over financing and titling. Similarly, Cybernetic Serendipity faced logistical issues: its planned tour to the Corcoran Gallery was cancelled after damage during transit. Jasia Reichardt publicly disowned the Washington D.C. version, citing mishandling.

These setbacks fuelled scepticism in the press and highlighted the tensions between technological fragility and curatorial ambition. Burnham observed that many critics, especially those grounded in humanism, were sceptical of what they saw as the intrusion of technology into nature and tradition. Championing ‘hard technology as an aesthetic lifestyle’ risked damaging their credibility. Critics feared that computers could mechanise and thereby trivialise human creativity.[7]

Humanism vs Computation

A key cultural barrier was the perception that computers merely mimicked existing styles, replacing creativity with cold logic. French philosopher and engineer Abraham Moles commented that computer art resembled a ‘Neomannerism of the computer,’ where ‘procedure is more important than form.’[8] The final image became a demonstration of code rather than an object of contemplation—central to Reichardt and Burnham’s thesis but alienating to critics steeped in Modernist aesthetics.

Burnham’s notion of art as a system rather than object conflicted with the entrenched materialism of the art market. His hypertextual conception of discourse—where meaning arises through associative links—liberated artists from artefact-centric thinking, but undermined traditional structures of artistic evaluation.

For many, the machine lacked the emotive or cultural depth necessary for art. In the public imagination, computers were instruments of military control, operated by anonymous figures in lab coats or fatigues. This imagery, especially during the Vietnam War and Cold War tensions, fuelled widespread resistance.

Militarisation and Moral Resistance

Computer art’s militaristic associations damaged its reception. Critics and viewers alike were uneasy with the transformation of wartime technologies into cultural artefacts. Australian art historian Grant Taylor remarked that ‘the notion of art made by computer aroused a surprising degree of hostility,’ especially among those already disenchanted with modern art’s alleged dehumanisation.[9] Cybernetic systems used in Vietnam—like those that failed to accurately target bombing—only intensified this perception.

Yet a digital counterculture emerged, particularly in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district, where artists repurposed computers for emancipatory goals. Despite its eventual absorption into Silicon Valley’s techno-capitalism, this movement left its imprint on both Cybernetic Serendipity and Software.

Nevertheless, artists such as Frieder Nake voiced concern over the increasing entanglement of computing with Cold War politics. In a 1971 PAGE bulletin, Nake lamented that the computer ‘contributed very little to aesthetic behaviour.’[10] Disillusioned, he ultimately abandoned the field.

Jonathan Benthall echoed this sentiment, noting that rapidly evolving operating systems rendered artists’ technical skills obsolete, threatening the sustainability of computer art practice. Charlie Gere added that artists were ‘just finding out what it can do,’ suggesting early experimentation lacked depth. As Benthall observed, real innovation would only emerge when artists applied computational thinking beyond the machine itself.[11]

Systems Thinking and Conceptual Art

Computer art’s systemic logic found common ground with conceptualism. Software paralleled Information (MoMA, 1970), curated by Kynaston McShine. Artists like Hans Haacke appeared in both, using cybernetic principles to critique institutions. His News and Visitors’ Profile, part of his Real-Time Systems, embodied the fusion of political engagement and technological experimentation inspired by Burnham’s theories.

Despite this overlap, the critical establishment failed to recognise these shared logics. Computer art’s multiplicity—encompassing poetry, music, graphics, and literature—compounded the challenge. Artists were scientists, engineers, or programmers, defying art-historical categorisation.

Classification, Change, and Canonical Exclusion

The pace of technological change further destabilised critical reception. Unlike oil painting or sculpture, digital practices evolved too rapidly for stable definition. Taylor notes that art historians ‘preferred subjects that evolved at a manageable pace.’[12] Without a cohesive aesthetic language or geographic centre, computer art lacked the unifying characteristics typical of modernist movements. Although institutions like the Computer Arts Society (UK, 1969), SIGGRAPH, Ars Electronica, and Art Basel would later emerge, their influence came too late to position early computer art within canonical modernism.

Theoretical complexity, coupled with rapid obsolescence, made computer art resistant to traditional art-historical frameworks. Its overlapping theoretical terrain—cybernetics, systems theory, information theory—created confusion and distanced it from mainstream criticism. Burnham’s own retreat from systems aesthetics, due to its complicity with military and commercial interests, left the field without a strong theoretical advocate.

Commodification and Aesthetic Prejudice

The art market’s valuation of sign and provenance further alienated computer art. Jean Baudrillard argued that during capitalism’s ascendancy, aesthetic value became increasingly tied to commodity exchange.[13] Despite efforts to dematerialise the object and challenge market hierarchies, computer art was often dismissed once its mechanical origins were revealed. Taylor observed that the use of computers was ‘the kiss of death’ when seeking gallery representation.[14]

Manfred Mohr, a German pioneer of computer art, recounted that people ‘threw eggs at me. They said I was destroying art.’ At that time, he said, ‘the computer was like pornography.’[15] Such anecdotes underscore how computer art transgressed the unwritten codes of cultural legitimacy.

Historical Erasure and Misremembering

Despite Software and Cybernetic Serendipity being crucial early landmarks, they are rarely included in major retrospectives. Burnham’s Systems Esthetics appeared in the catalogue for Donna De Salvo’s Open Systems: Rethinking Art c.1970—yet the exhibition included no actual computer art. As Charlie Gere recalled: ‘When we asked Donna De Salvo where’s all the art that was actually using systems, she said she didn’t know about it!’[16]

This erasure, Gere argues, was a symptom of persistent cultural suspicion. Computer art’s links to ‘engineering and maths’ made it seem mechanistic and lacking in human values. Yet in 1970 Burnham presciently wrote:

‘Information processing technology influences our notions about creativity, perception and the limits of art. It is probably not the province of computers… to produce works of art as we know it; but they will… redefine the entire area of aesthetic awareness.’[17]

Conclusion: From Margins to Legacy

Computer art did not disappear; it metamorphosed. Its influences re-emerged in the 1990s and 2000s as algorithmic art, net art, generative art, and bio art. These multidisciplinary practices do not negate computer art’s early promise but confirm its legacy. Video art, installation, and sound practices have also drawn from the systems logic first explored in Cybernetic Serendipity and Software.

This post has shown that the marginalisation of computer art was not due to its lack of value but to a complex interplay of critical conservatism, technological suspicion, institutional inertia, and ideological bias. Its exclusion from the canon was a cultural decision—one now being slowly reversed as digital aesthetics reshape contemporary practice.

[1] Charlie Gere, interviews in original source.

[2] Jack Burnham, quoted from original material.

[3] Michael Shepherd, Sunday Telegraph review.

[4] Evening Telegraph, August 1968.

[5] New York Times review.

[6] Jack Burnham.

[7] Burnham, various interviews.

[8] Abraham Moles, PAGE 28.

[9] Grant Taylor.

[10] Frieder Nake, PAGE 18 (1971).

[11] Jonathan Benthall; Charlie Gere.

[12] Grant Taylor.

[13] Jean Baudrillard.

[14] Grant Taylor.

[15] Manfred Mohr, interview in The White Review.

[16] Charlie Gere.

[17] Jack Burnham, 1970.

Refs

Baudrillard, Jean, 1983. Simulations (USA: MIT Press).

Benthall, Jonathan, 1971. ‘Technology and Art’, http://www.bbk.ac.uk/hosted/cache/archive/CAS/Benthall,%20J.%20Technology%20and%20Art.%20Studio%20International.%20March%201969%20p112.pdf [Accessed 6 September 2020].

Burnham, Jack, 1970. ‘Notes on Art and Information Processing’, in Jack Burnham, ed.,1970. Software: An Exhibition (New York: The Jewish Museum), pp. 10-14.

Burnham, Jack, 1973. The Structure of Art (New York: George Braziller).

Burnham, Jack, 1974. Great Western Salt Works (New York: George Braziller).

Burnham, Jack, 1980. ‘Art and Technology: The Panacea That Failed’, https://monoskop.org/images/4/4e/Burnham_Jack_1980_Art_and_Technology_The_Panacea_That_Failed.pdf [Accessed 17 August 2020].

Gere, Charlie, 2020. Interview on Computer Art. Interviewed by Andrew Welsby. 17 August 2020, 13:00.

Lieser, Wolf, 2020. Research Dissertation, [email] Message to A. Welsby (andy.welsby@me.com). Sent 13 August 2020: 10:03. [Accessed 13 August 2020].

Mohr, Manfred, 1973. ‘Using a Computer in The Visual arts Means Amplifying The Possibilities of Intellectual and Visual Experience’, PAGE 28: Bulletin of the Computer Arts Society, January. http://emohr.com/articles-biblio/ComputerArtsSociety_Page28_London1973.pdf [Accessed 7 September 2020].

Moles, Abraham, 1973. ‘Some Remarks About Art and Computer’, PAGE 28: Bulletin of the Computer Arts Society, January. https://computer-arts-society.com/uploads/page-28.pdf [Accessed 7 September 2020].

Nake, Frieder, 1971. ‘There Should Be No Computer Art’, PAGE 18: Bulletin of the Computer Arts Society, October. http://www.bbk.ac.uk/hosted/cache/archive/PAGE/PAGE18.pdf [Accessed 6 September 2020].

Shepherd, Michael, 1968 ‘Machine Mind?’, Sunday Telegraph, 11 Aug, p. 12. The Telegraph Historical Archive, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/IO0709169098/TGRH?u=tou&sid=TGRH&xid=b9fc7459 [Accessed 7 September 2020].

Taylor, Grant, D., 2013. ‘The Soulless Usurper: Reception and Criticism of Early Computer Art’ http://www.emohr.com/articles-biblio/mainstreamExperimentalismChapter1Excerpt.html [Accessed 20 July 2020].

Taylor, Grant, D., 2014. When the Machine Made Art: The Troubled History of Computer Art (New York: Bloomsbury).

Unknown, 1968. ‘Serendipity by Technology is an Art’, The Evening Telegraph, 20 August, p. 16. https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0000769/19680820/161/0016 [Accessed 3 September 2020].

Leave a comment