Part 2: Art, Technology, and Ideology

In 1971, Jasia Reichardt described computer art as a ‘movement that is international, motivated by the use of media, technique and method, rather than ideology.’ [1] This post explores the extent to which two landmark exhibitions—Cybernetic Serendipity and Software—can nevertheless be understood through an ideological lens. While recognising that the curatorial motivations behind each exhibition were distinct, this post challenges the notion that such shows are ideologically neutral. Rather than rendering curation invisible or fully deterministic, this analysis attempts to balance the explicit intentions of the organisers with the retrospective insight afforded by historicism.[2] Positioned within the Cold War context, these exhibitions may be seen as cultural artefacts reflecting and advancing political and economic ambitions in both the United Kingdom and the United States.

Art as Ideological State Apparatus

This analysis draws on the theoretical framework of French Marxist philosopher Louis Althusser (1918–1990), who contends that political hegemony is ‘indispensable to the reproduction of capitalist relations of production.’[3] From this perspective, cultural institutions and exhibitions function as Ideological State Apparatuses (ISAs), subtly persuading viewers of the necessity and legitimacy of technological advancement.[4] Cybernetic Serendipity and Software can therefore be read as cultural mechanisms for validating emerging technologies, aiming to establish a set of shared values and social norms in alignment with capitalist progress.

Key themes uniting both exhibitions include the dematerialisation of the art object and the challenge to traditional reception modes.[5] These shows invited audiences to reimagine their relationship to art, to information, and to their own sense of agency. However, such invitations occurred within a broader ideological framework that sought to normalise computing as a progressive, indispensable tool for industrial and cultural renewal. Notably, the technologies underpinning computer art often stemmed from military research. Unlike traditional art histories that treat such contexts as peripheral, this post foregrounds them: artists frequently repurposed military hardware to construct the tools of early computer art.

Exhibitions as Sites of Public Ideology

Both Cybernetic Serendipity and Software were group exhibitions, reaching diverse publics rather than specialist art audiences. Unlike canonical monograph shows, these exhibitions offered opportunities for curatorial experimentation and broader engagement. Temporary as they were, the exhibitions made private curatorial intentions public, often reinforcing bourgeois authority under the guise of democratic access.[6] Thus, the exhibition format became not just a vehicle for distribution but also a crucible for the ideological negotiation of computer art’s meaning and legitimacy.[7]

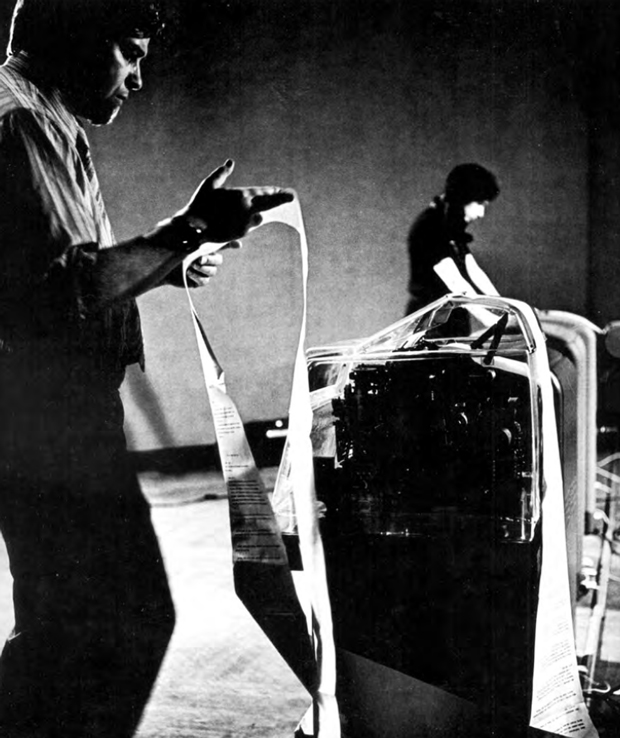

Curatorial concerns in both exhibitions revolved around art’s place in the canon. Rather than emphasising material production, the curators foregrounded how art could express relational systems and environments.[8] Reichardt claimed that computers democratise art, ‘amplifying happiness and promoting pleasure,’[9] while Burnham focused on the dematerialisation of the art object and the rise of systems aesthetics.[10] Burnham’s Software included Ned Woodman and Theodor H. Nelson’s Labyrinth: An Interactive Catalogue (1970)[11] and Sonia Sheridan’s Interactive Paper System(1969–70)[12], both of which invited user participation and undermined the notion of a singular, authentic artwork. Sheridan’s use of a 3M Thermofax machine, for example, turned everyday objects into reproducible artworks, echoing Walter Benjamin’s critique of the art object’s aura.

Systems Theory and Dematerialisation

Charissa Terranova observes that traditional ontologies of art-making were disrupted by the mediation of machines.[13]Burnham contrasted the ‘finite’ objects of high art with emergent ‘unobjects’ of computer art, informed by cybernetic feedback loops and a broader countercultural engagement with ecology and kinesthetics.[14] His 1968 essay Systems Esthetics argued for a shift from object-based art to aesthetic systems. [15] For Burnham, art became a code or flow of information rather than a medium-specific product, reflecting a post-formalist sensibility already present in the late 1960s. [16]

Burnham wrote in the Software catalogue: ‘Software is about experiencing without mental cues of art history.’[17]Works like Les Levine’s A.I.R. (1968–70) captured artists at work via television, aiming to collapse the boundary between art and everyday culture. Levine argued: ‘The experience of seeing something first-hand is no longer of value in a software-controlled society.’[18] For Burnham, viewers should ‘sense your responses when you perceive in a new way,’[19] aligning art with the theories of cyberneticist Norbert Wiener and biologist Ludwig von Bertalanffy.

Yet this emphasis on information as aesthetic material has drawn later criticism. N. Katherine Hayles warned of reducing human complexity to a reified concept of ‘information,’[20] while Reinhold Martin noted the emergence of post-war technological systems that diverged from traditional Gemeinschaft social relations.[21] Exhibitions, in this sense, become sites of special power—capable of either being contained or exploited, as W.J.T. Mitchell argues.[22]

Education, Play, and the Art ISA

Althusser names education as the primary ISA of the bourgeois state.[23] Both exhibitions, particularly Cybernetic Serendipity, incorporated educational and playful elements aimed at children and families. Gordon Pask’s Colloquy of Mobiles (1968) encouraged interaction through light, sound, and movement—play that masked its foundations in serious cybernetic theory.[24] For Pask, the work initiated cooperation and learning, modelling systems of communication.[25] Lars Bang Larsen suggests such experiences shape children’s early social identities, assigning new value to technological agency within society.[26]

However, such interactivity may represent what Althusser terms a ‘sleight-of-hand’ offering imagined agency while reproducing dominant ideology. The didactic and accessible nature of the exhibitions thus supported a broader ideological transformation—from public suspicion of computers to their enthusiastic adoption.

Military Origins and Cultural Amnesia

The historical roots of computer art lie not in normative art trajectories but in military innovation. Computers and Automation, a trade journal that inspired Reichardt, awarded early computer art prizes to the U.S. Army Ballistics Research Labs. Their winning image, Splatter Diagram, visually analogised projectile trajectories. Desmond Paul Henry, whose drawing machine was featured in Cybernetic Serendipity, built it from an analogue computer originally used to calculate bomb sights.[27]

Artists often distanced themselves from this uncomfortable genealogy. Charlie Gere notes that some refused to engage with technology, rejecting its technocratic and militaristic origins.[28] John von Neumann’s IAS machine, used to model H-bomb calculations, epitomises the military foundation of digital computing. George Dyson has remarked that computer art emerged from a ‘deal with the devil’: in return for building weapons, scientists gained access to powerful machines.[29]

Technological Optimism and the Softening of Fear

Despite their origins, the exhibitions projected an optimistic, even playful image of computing. Wilson’s 1964 call for modernisation ‘forged in the white heat’ of technology resonated with Cybernetic Serendipity’s cheerful tone. [30] As Frieder Nake noted, the exhibition opened during geopolitical unrest—the invasion of Czechoslovakia by the Warsaw Pact—yet offered a disarming experience.[31] ICA’s Leslie Stack stated: ‘We want people to lose their fear of computers by playing with them.’[32] The exhibition thus repackaged militarised technology as creative potential.

Adorno and Horkheimer’s critique of the culture industry applies here: popular appeal may render audiences passive, reinforcing the hegemony of technological rationalism.[33] Museums, as Donald Preziosi argues, shape value systems and social identities, legitimising dominant ideologies.[34] The Evening Standard noted that Cybernetic Serendipity pleased both “hippies” and ‘schoolboys’—a testament to its wide-reaching ideological appeal.[35]

Conclusion

It would be reductive to cast Cybernetic Serendipity and Software merely as handmaidens to state power. This post has shown that while curators such as Reichardt and Burnham asserted autonomy and optimism in their visions, these exhibitions also functioned as ideological apparatuses. The reception of the artworks was shaped by dominant social narratives, offering viewers an imagined agency while reinforcing a broader capitalist agenda that sought to normalise computer technology.[36]

As Paul O’Neill notes, exhibitions are not neutral containers but ‘subjective political tools’ that express identity and ideology.[37] Within the Cold War milieu, these exhibitions smoothed the cultural entry of computing into everyday life, softening its military associations and recasting it as a democratic and creative force. Yet even in their playfulness, they contributed to the reproduction of hegemonic values, defining what art could be—and who the future users of technology would become.

Refs

Althusser, Louis, 1970. Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses (France: La Pensée) http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/althusser/1970/ideology.htm [Accessed 2 September 2020].

Basualdo, Carlos, 2008. ‘The Unstable Institution’, Zentrum Für Kust und Medien Karlsruhe, July. https://zkm.de/de/carlos-basualdo-the-unstable-institution [Accessed 12 September 2020].

Burnham, Jack., 1968b. ‘System Esthetics’, Art Forum, Vol. 7, No. 1. https://monoskop.org/images/0/03/Burnham_Jack_1968_Systems_Esthetics_Artforum.pdf [Accessed 4 May 2020].

Burnham, Jack, 1974. Great Western Salt Works (New York: George Braziller).

Gere, Charlie, 2008. Digital Culture, 2nd ed. (UK: Reaktion Books).

Fernández, María, 2008. ‘Detached From HiStory: Jasia Reichardt and Cybernetic Serendipity’, Art Journal: New York, Vol. 67, No. 3, pp. 7-24. https://search-proquest-com.libezproxy.open.ac.uk/hnpguardianobserver/docview/223297209/9FF2174C5DBE499APQ/3?accountid=14697 [Accessed 7 September 2020].

Fernández, María, 2008. ‘Gordon Pask: Cybernetic Polymath’, Leonardo, Vol. 41, pp 162-168. https://www-mitpressjournals-org.libezproxy.open.ac.uk/doi/pdf/10.1162%2Fleon.2008.41.2.162 [Accessed 3 August 2020].

Halsall, Francis, 2008. ‘System Aesthetics and the System as Medium’, http://systemsart.org/halsall_paper.html [Accessed 14 August 2020].

Hayles, Katherine, N., 1999. How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature and Information (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

Henry, Desmond, P., 1968. ‘The Henry Drawing Computer’, in Jasia Reichardt, ed., 1968. Cybernetic Serendipity: the Computer and the Arts (London: Studio International), p. 50.

Larsen, Lars Bang, 1999. ‘Social Aesthetics’, in Claire Bishop, ed., 1999. Participation: Documents of Contemporary Art (USA: MIT Press & Whitechapel Gallery), pp. 172-183.

Levine, Les, 1969. ‘Systems Burn-off X Residual Software’, in Jack Burnham, ed., 1970. Software: An Exhibition (New York: The Jewish Museum), p. 61.

Nelson, Theodor, H. and Woodman, Ned, 1970. ‘Labyrinth: An Interactive Catalogue’, in Jack Burnham, ed., 1970. Software: An Exhibition (New York: The Jewish Museum), p. 18.

Mitchell, W. J. T., 1986. Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press).

O’Neill, Paul, 2007. ‘The Curatorial Turn: From Practice to Discourse’, in Judith Rugg, and Michèle Sedgwick, eds, Issues in Curating Contemporary Art and Performance, pp. 13-28. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/open/reader.action?docID=329916&ppg=12 [Accessed 24 August 2020].

Nake, Frieder, 1971. ‘There Should Be No Computer Art’, PAGE 18: Bulletin of the Computer Arts Society, October. http://www.bbk.ac.uk/hosted/cache/archive/PAGE/PAGE18.pdf [Accessed 6 September 2020].

Terranova, Charissa, N., 2014. ‘Systems and Automatisms:

Jack Burnham, Stanley Cavell and the Evolution of a Neoliberal Aesthetic’, Leonardo, Vol. 47, No. 1, pp 56-62. https://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1162/LEON_a_00703 [Accessed 4 August 2020].

Pask, Gordon, 1968.’ The Colloquy of Mobiles’, in Jasia Reichardt, ed., 1968. Cybernetic Serendipity: The Computer and the Arts(London: Studio International), pp. 34-35.

Reichardt, Jasia, 1968. ‘Introduction’ in Jasia Reichardt, ed., 1968. Cybernetic Serendipity: the Computer and the Arts (London: Studio International), pp. 5-8.

Reichardt, Jasia, 1971. ‘Cybernetics, Art and Ideas’, in Jasia Reichardt, ed., 1971. Cybernetics, Art and Ideas (New York: New York Graphic Society), pp. 7-17.

Usselmann, Rainer, 2003. ‘The Dilemma of Media Art: Cybernetic Serendipity at the ICA London’, Leonardo, Vol 36, No. 5, pp. 389-396. http://dada.compart-bremen.de/docUploads/36.5usselmann.pdf [Accessed 8 June 2020].

[1] Reichardt, 1971: p. 7.

[2] Basualdo, 2008.

[3] Althusser, 1970: p. 22.

[4] O’Neill, 2007: p. 16.

[5] O’Neill, 2007: p. 14

[6] O’Neill, 2007: p. 14

[7] O’Neill, 2007: p. 15.

[8] Burnham, 1974: p. 17.

[9] Reichardt, 1971: p. 17.

[10] Terranova, 2014: p. 60.

[11] Nelson and Woodman, 1970: p. 18.

[12] Sheridan, 1970, p. 24.

[13] Terranova, 2014: p. 57.

[14] Burnham, 1968: p. 31.

[15] Burnham, 1968: p. 31.

[16] Halsall, 2008

[17] Burnham, 1968b.

[18] Levine, 1970: p. 62.

[19] Burnham, 1968: p. 10.

[20] Hayles, 1999: p. 54.1st Aug

[21] Terranova, 2014: p. 57.

[22] Mitchell, 1986: p. 151.

[23] Moxey, 2013: p. 139.

[24] Fernández, 2008: p. 166.

[25] Fernández, 2008: p. 166.

[26] Larsen, 1999: p. 174.

[27] Reichardt, 1968: p. 5.

[28] Gere, 2008: p. 177.

[29] Kelly, 2012.

[30] Francis, 2013.

[31] Interview with Nake, 20 August 2020.

[32] Ussellman, 2003: p. 391

[33] Richter, 2020: p. 10.

[34] Marstine, 2005: p. 2.

[35] Unknown, 2015: p. 7.

[36] Althusser, 1992: p. 957.

[37] O’Neill, 2007: p. 16.

Leave a comment