Introduction

At first glance, the strobing screens of a club night and the subdued glow of a gallery installation might appear worlds apart. Yet both are immersed in the language of light, rhythm, and moving images. From the mid-twentieth century onwards, video art carved a place within institutional frameworks, celebrated for its conceptual rigour and technological experimentation. In parallel, VJing evolved as a live visual practice within underground clubs and raves—often dismissed as ephemeral or purely entertainment-based.

In this article, drawing from my own practice across both fields, I ask whether VJing might be the last major underground art form to be absorbed into the fine art canon. I begin by outlining my personal journey from early digital image-making to my time as a VJ, before briefly contextualising VJing and video art as distinct yet overlapping fields. I argue that despite VJing’s historic marginalisation due to its performative, informal and nightlife-based origins, it has profoundly shaped the immersive aesthetics and real-time sensibilities of contemporary media art (Lovejoy, 2004; Shanken, 2009).

VJing: A Parallel Underground History

While video art ascended into institutional spaces and white-cube galleries, VJing evolved along a parallel, underground trajectory—emerging from the shadows of dance floors, warehouses, and club culture. Rooted in the ephemeral environments of nightlife and rave culture, VJing developed as a live, audience-responsive form of visual performance. Unlike the fixed, installation-based formats of gallery video art, VJing embraced improvisation, real-time feedback, and collective energy.

In Britain, the 1980s Scratch Video movement, primarily associated with politically radical, media-savvy artists who used rapidly-edited video to critique television, consumerism, and mass media culture, laid early foundations for this form, remixing broadcast footage with subversive intent (Spinrad, 2005). By the 1990s, VJing had become an integral feature of techno parties and raves, with practitioners generating abstract, rhythmic imagery to complement DJ sets. Collectives such as Hexstatic, Addictive TV, and Coldcut pioneered hybrid approaches, blending visual sampling, political commentary, and pop culture in performances that rivalled the innovation of their audio counterparts.

Crucially, VJs often operated outside the structures of the art world, developing their own tools and aesthetics. Many repurposed video mixers, created custom patches in software like Max/MSP, or coded their own visual engines. As digital technology advanced, platforms like VJamm, Resolume, and Modul8 enabled more complex live compositions, giving rise to a generation of artists who viewed the screen as a performative canvas rather than a passive display.

Despite its technological ingenuity and cultural relevance, VJing has historically been overlooked by art institutions and critics. Its roots in club culture and association with entertainment often led to its marginalisation in academic and curatorial discourse, especially when compared to the canonised practices of video art (Parikka, 2012). Yet, as audiovisual performance and immersive media gain institutional legitimacy, VJing’s influence on contemporary moving image culture becomes increasingly difficult to ignore.

VJing and livevevil

My journey as a VJ and time-based artist began in 1997, a moment situated at a significant transitional point in the evolution of digital media. At the time, I was studying AutoCAD at college, where I was introduced to a suite of desktop-based design tools including Adobe Photoshop, Premiere, and Aldus PageMaker. These early experiences, in hindsight, sit at the convergence of print, photographic, and cinematic traditions within digital workflows—a moment richly resonant from a media archaeological perspective (Elsaesser, 2016). This period not only opened a gateway to image-making through digital means but also foregrounded the material limitations of the era: non-realtime rendering, clunky interfaces, and restricted memory shaped how and what I could create.

In 1998, I enrolled in a Digital Art course which provided extended access to institutional workstations and licensed software. This allowed me to fully immerse myself in video editing and effects, often pushing the limits of what the hardware could handle. My approach during this period was largely formalist: I was fascinated by the manipulation of light and form through time. Eschewing traditional narrative, I explored temporal transformations and abstract rhythms—a sensibility more closely aligned with expanded cinema and early video art than with the dominant logics of commercial media (Rees, 1999). In retrospect, these works function as media archaeological gestures: materially shaped by their moment while critiquing dominant screen culture through duration, abstraction, and anti-spectacle aesthetics.

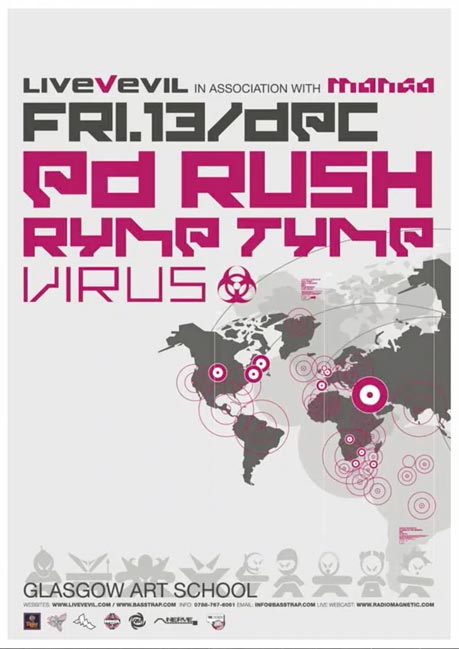

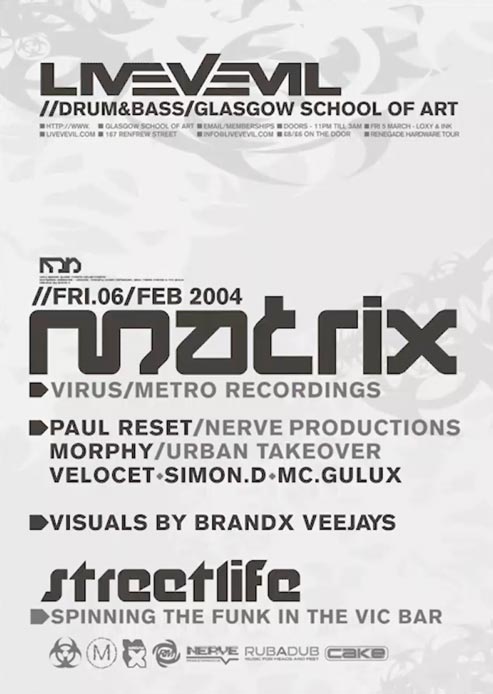

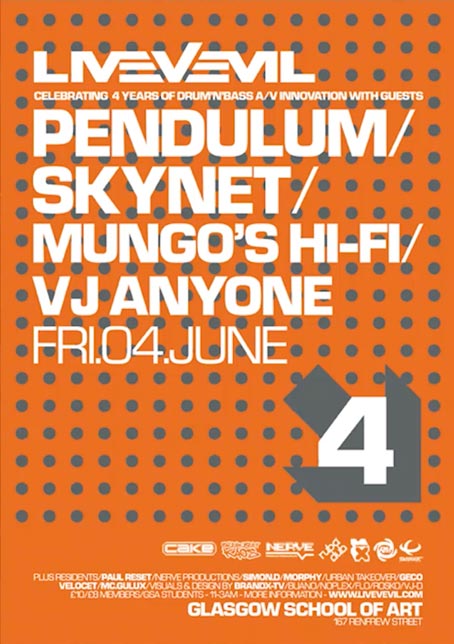

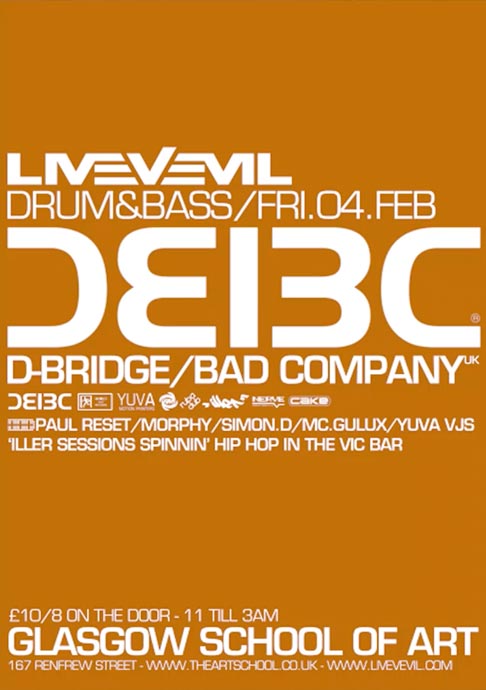

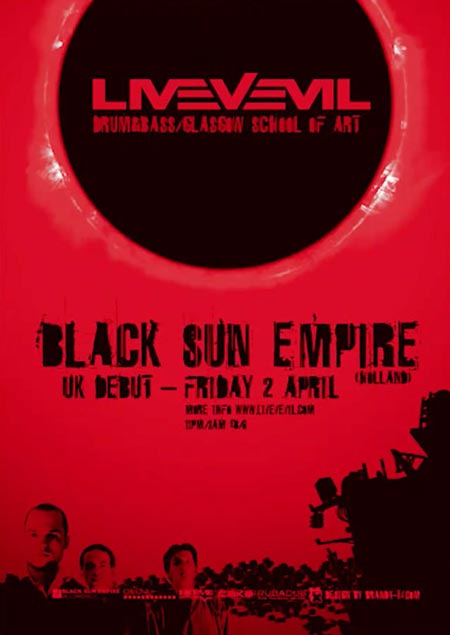

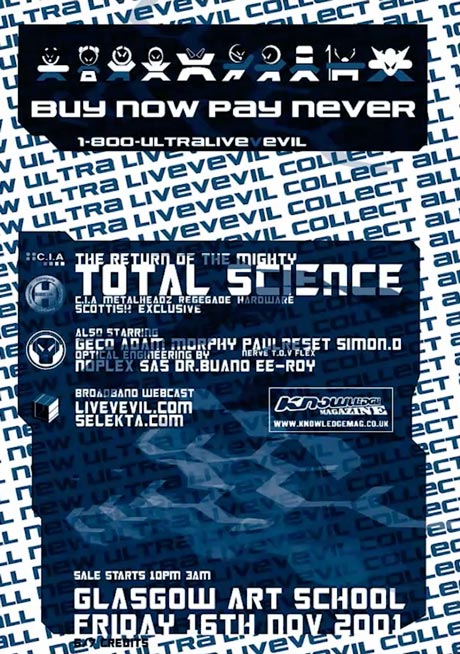

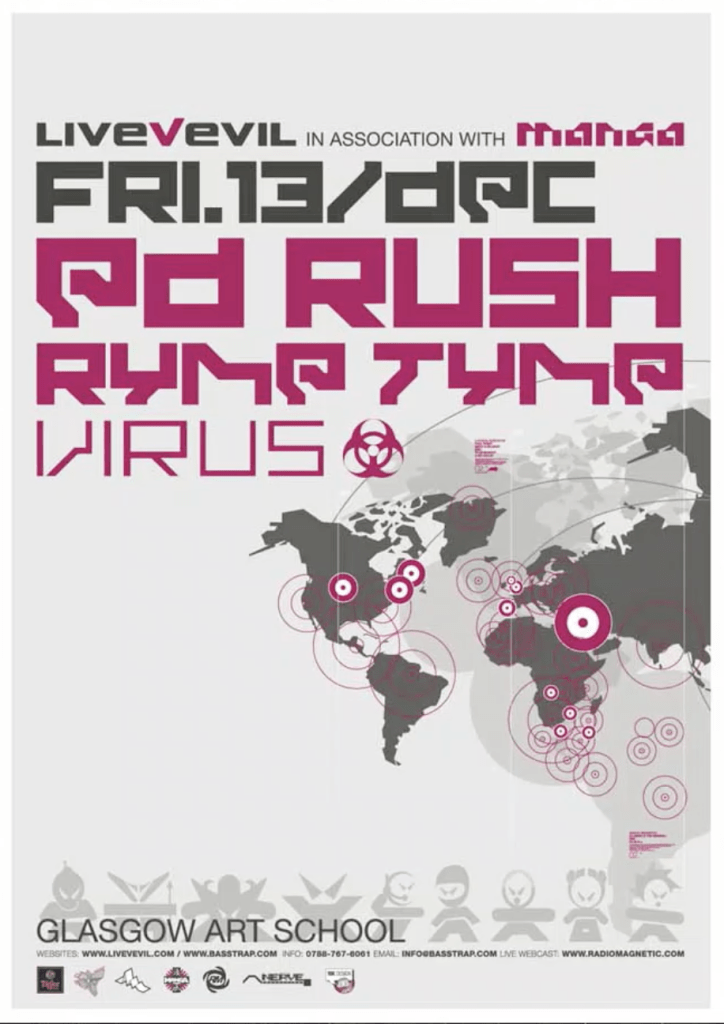

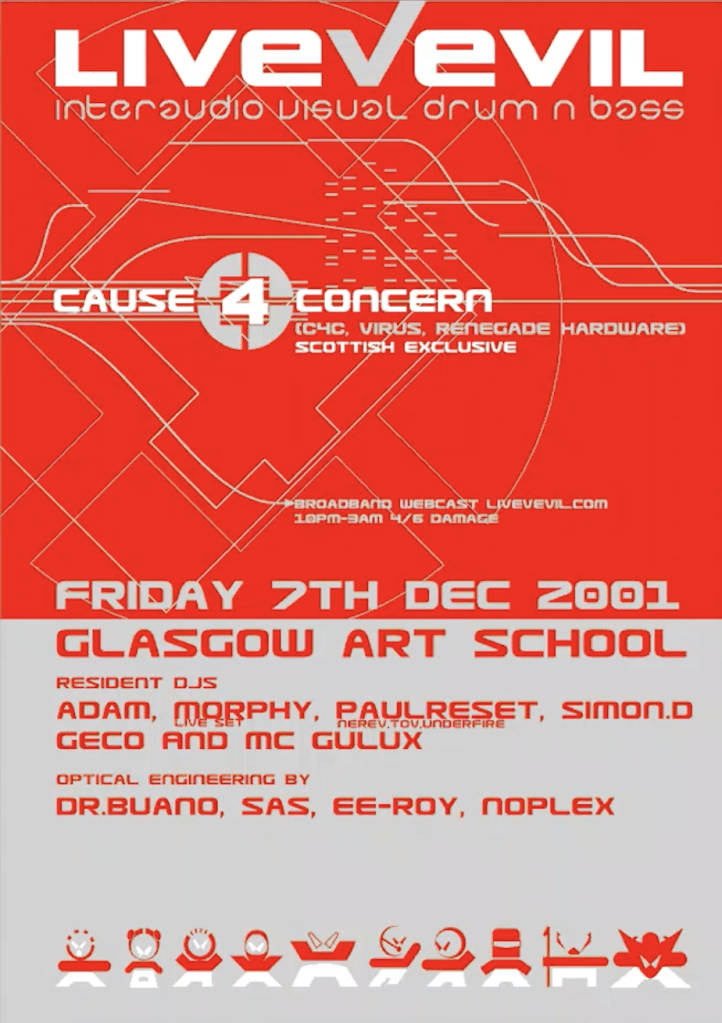

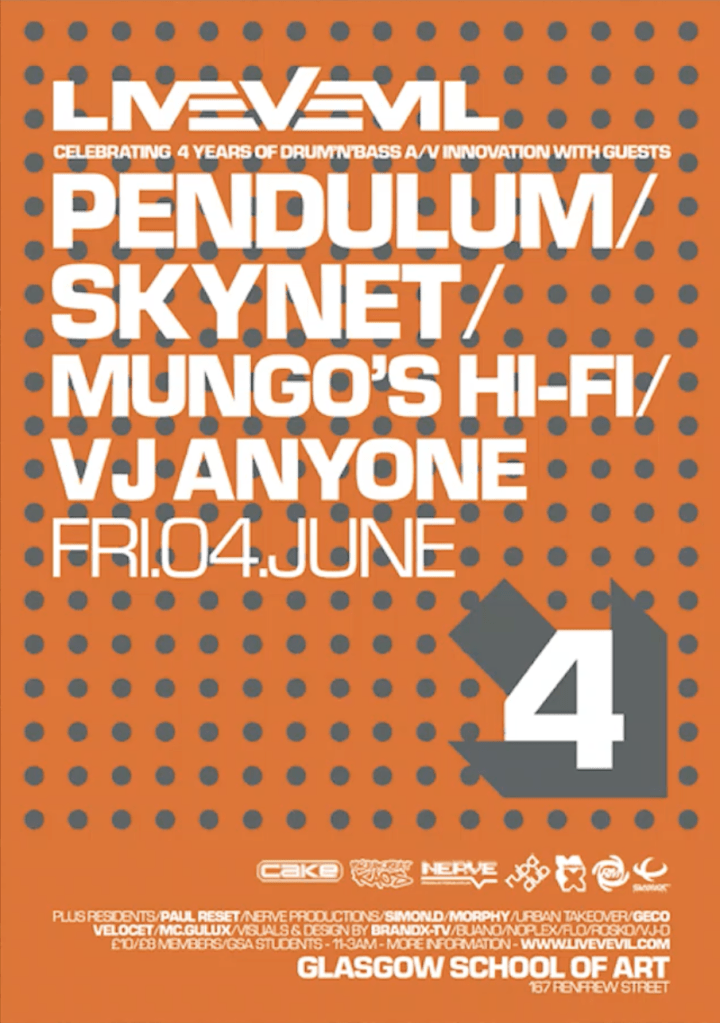

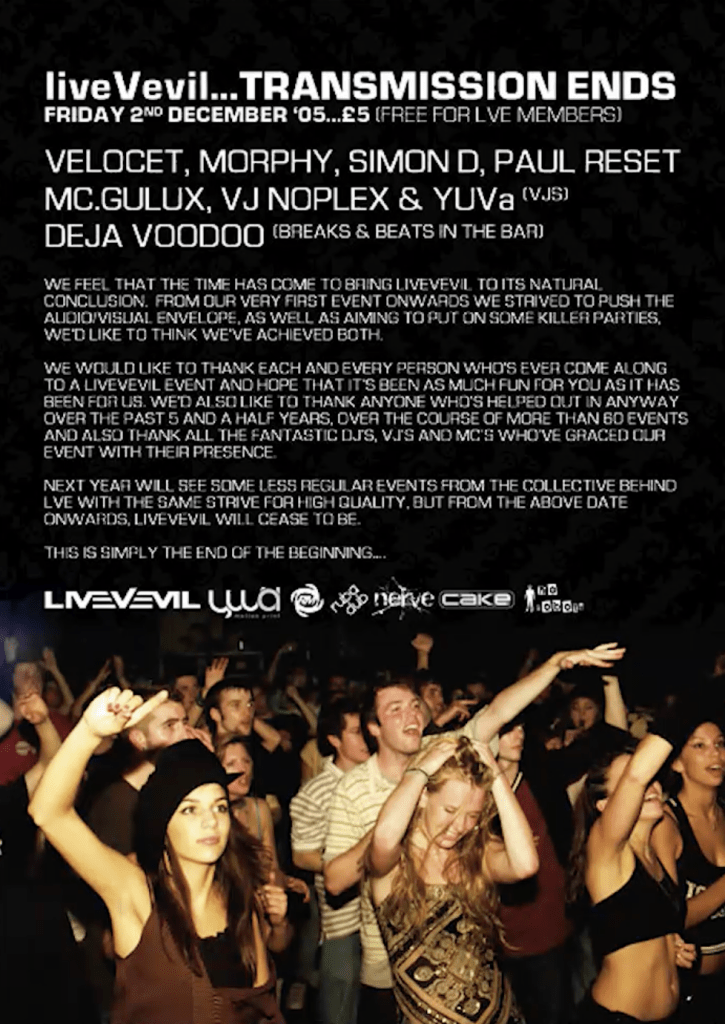

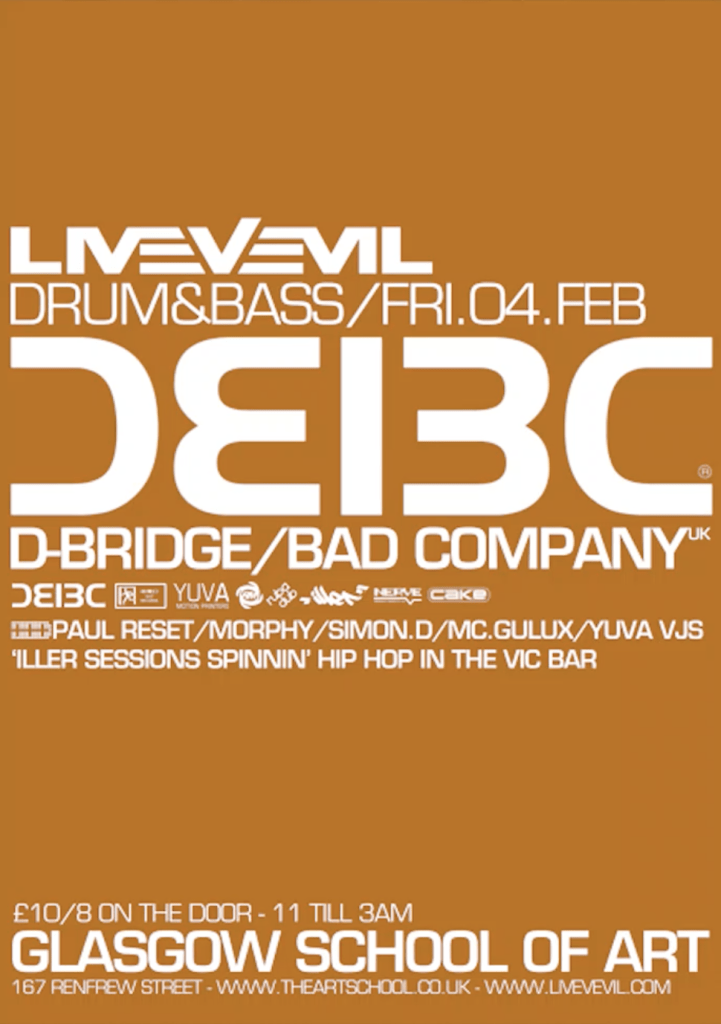

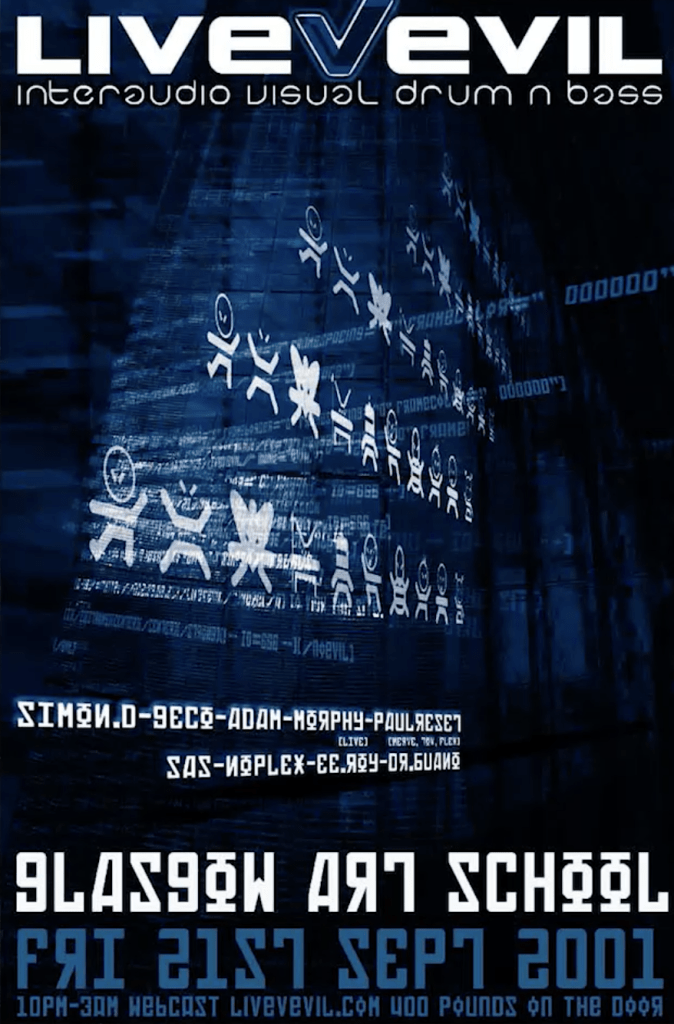

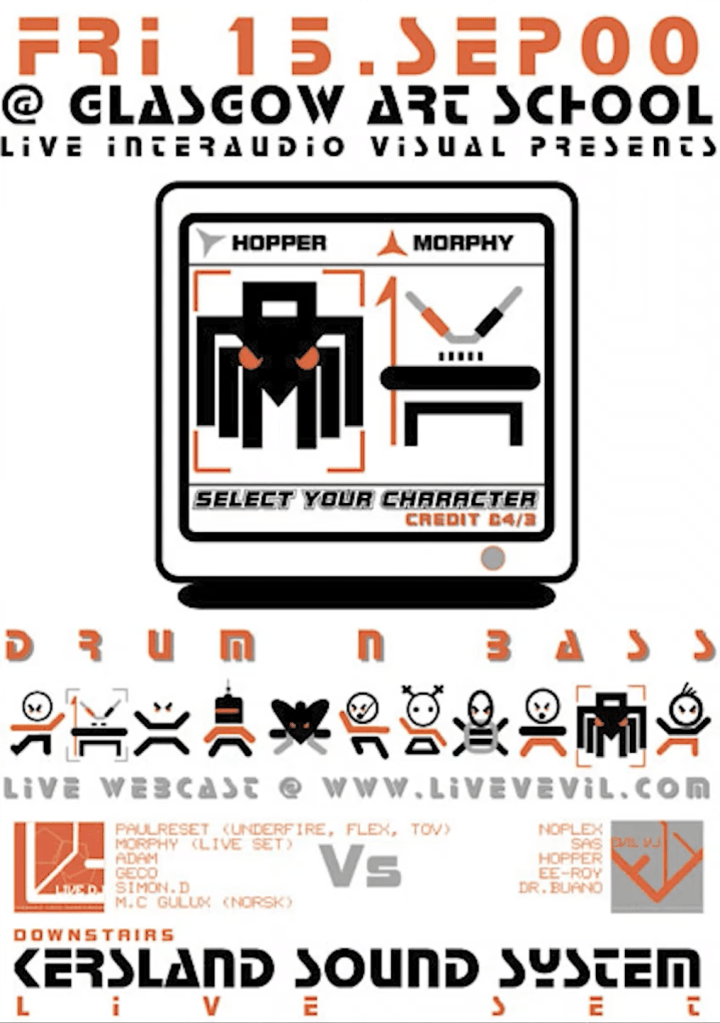

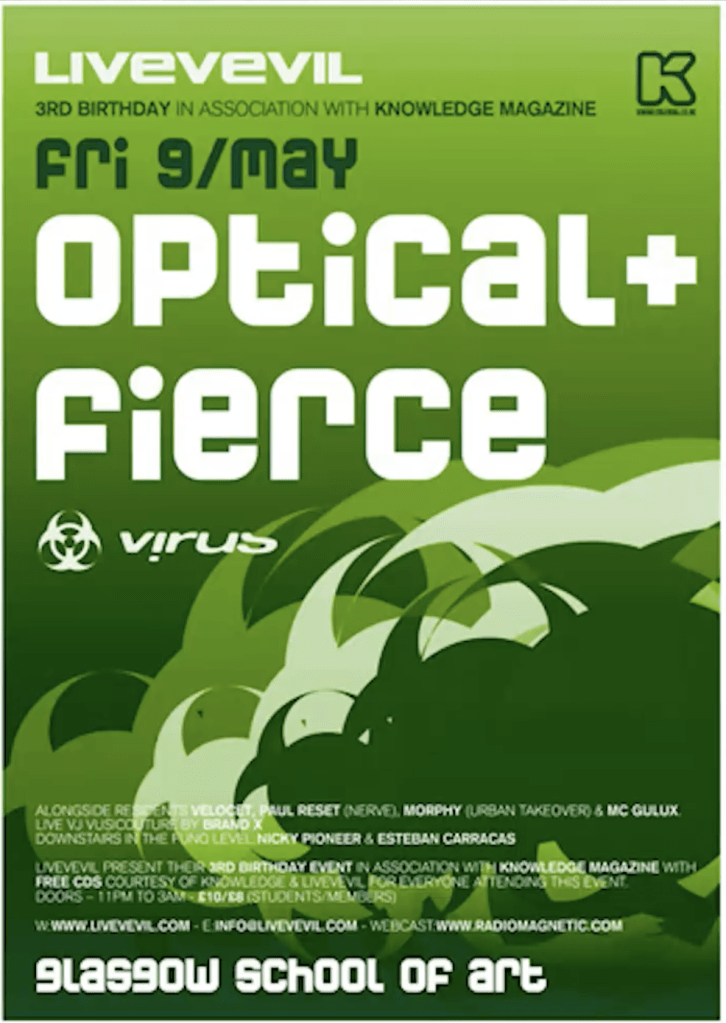

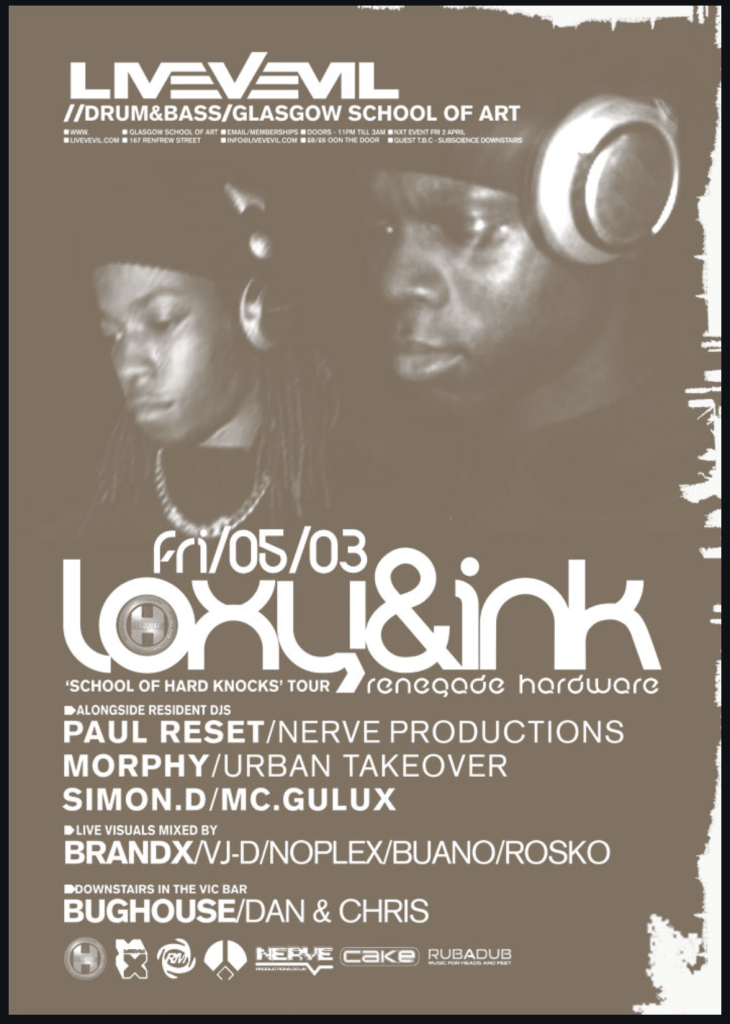

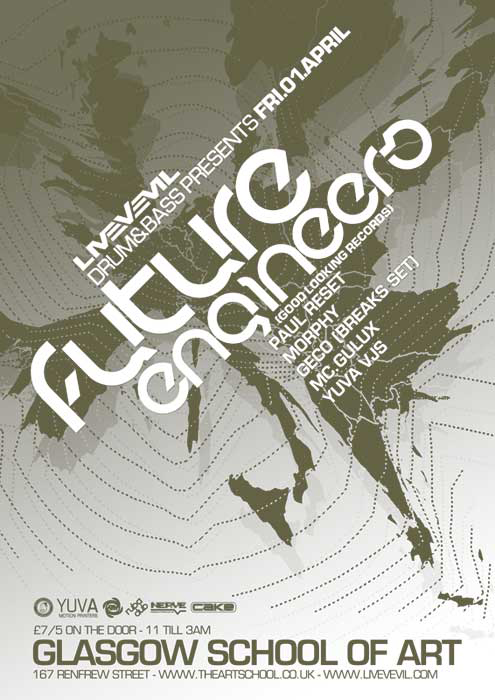

Over ten years, I VJ’d at many events and clubs including Resonate, Urizon, Bughouse at the Sub Club, Drop Beats Not Bombs in Birmingham, The Big Chill in Herefordshire, Brand X in Glasgow’s Centre for Contemporary Art, The Renfrew Ferry, The Arches in Glasgow, and of course, as a resident VJ at livevevil. Between 2000 and 2005, I became a core member of livevevil, a pioneering club night in Glasgow’s drum and bass scene. livevevil was conceived as a platform to merge cutting-edge audio with bespoke visual art, creating a fully immersive experience. Its name—a palindromic play on “live” and “evil”—symbolised the duality of sensory engagement, with visuals and music granted equal footing in performance (McFadyan, n.d.). I performed under the name Noplex, working alongside fellow VJs El Buano (Nick Roy), VJD (Dan Roy), SAS (Justine Montford), and later Rosko (Ross Paterson). Our collective rejected the notion of visuals as mere backdrop; instead, we framed them as co-equal agents in an audiovisual phenomenological experience.

Images: Paul Reset; Nick Roy; Dan Roy

Visually, livevevil was known for its non-linear, abstract and process-based aesthetics. I initially deployed real-time hardware-based video mixing and processing, namely, multiple VCR’s and monitors playing clips I rendered to VHS video tape. Tapes were mixed with broadcast video equipment – almost always a Panasonic MX50 analogue-digital video mixer. Later, when Apple macBooks were affordable, software such as Vidvox’s Grid, VDVMX and Pure Data helped create live video collages that responded dynamically to the music. Using looped and manipulated footage, our work resonated with early traditions of structural film and visual music, as well as cybernetic feedback systems (Youngblood, 1970). These performances often transformed the club space into an immersive environment where audio and image were entangled in feedback loops of rhythm, light and architecture. Paul McFadyan, one of the club nights audio producers writes,

‘Between 2000 and 2005, a bunch of very skint but imaginative individuals put on a collection of audio/visual club nights called LiveVEvil, and attempted to bring some fun and quality drum’n’bass to The Art School, and various other venues… We tried to do things slightly differently by placing a huge importance on the visual aspects of the events, as well as the audio, with a team of VJs and DJs. We also streamed the events live online, which was quite an unusual thing to do back in 2000…’ (McFadyan, n.d.)

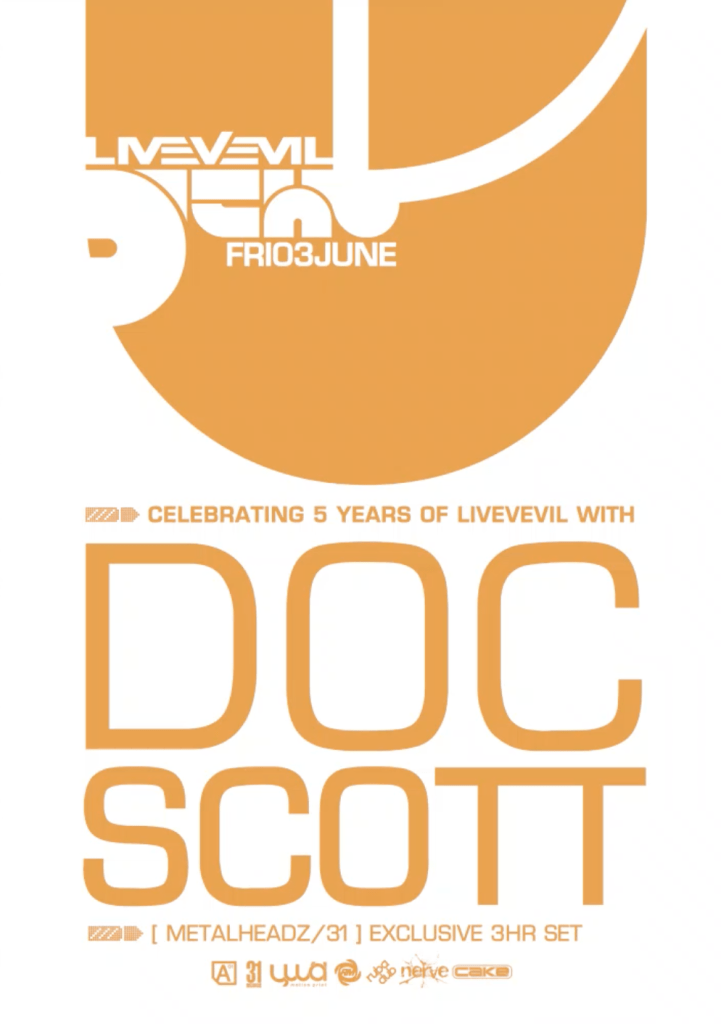

Informed by our participation in festivals and VJ events throughout the UK, our Glasgow-based collective—at various times called YUVA Motion Printers and earlier Brand X (after a show at the CCA)—sought to experiment with new audio-visual logics. This ethos placed us in productive tension with contemporaneous events. While Edinburgh’s Manga club night pursued more commercial trajectories, livevevil hosted artists like Photek, Doc Scott, Dom & Roland, and Black Sun Empire. Our visuals, projected at venues including Glasgow School of Art and The Arches, often exploited the architectural features of each site. Whether during a warehouse rave or a boat party on Loch Lomond, our goal was to embed the visual layer within the sonic and spatial structure of each event (Subvert Central, 2005).

Through over 60 events during its five-year lifespan, livevevil created an enduring legacy in Glasgow’s nightlife. In one landmark event, livevevil’s fifth birthday, Doc Scott delivered a three-hour set accompanied by VJ Anyone—an emblem of the sophisticated integration of audio and visual practices we had championed (Subvert Central, 2005). As Noplex, my practice helped lay the groundwork for what would eventually become more formally recognised within gallery, festival, and fine art contexts as “live media” or “real-time visuals.”

Looking back, my early work can be understood as both a product of and response to its technological moment. Working with limited render speeds, low resolutions, and analogue-digital hybrid setups, we created images that challenged the assumptions of dominant screen culture, particularly its linearity, its spectacle, and its detachment from liveness. By treating software, hardware, and venue architecture as collaborators, we crafted a practice that not only anticipated later immersive media aesthetics, but also situated itself within a lineage stretching from structural film and expanded cinema to the post-digital hybridity’s of today.

Video Art: The Canonisation of the Moving Image

As my VJ practice evolved I learned about the history, practice and acceptance of Video Art as a student of Time Based Art as an undergraduate student, and then Electronic Imaging as a Post-grad. Cinema has long dominated the visual culture of the 20th century, but by the 1960s, the development of accessible video technologies introduced a new artistic medium: video art. A key breakthrough came with Sony’s Portapak in 1965, a portable video recorder that empowered artists to produce moving image works outside of the institutional frameworks of film and television. Unlike traditional broadcast cameras, the Portapak was relatively affordable and lightweight, enabling artists and activists to document, perform, and experiment independently (Shapiro, 1981; Rush, 2003).

Video art initially emerged as an experimental and subversive practice. Artists like Vito Acconci, Joan Jonas, and Nam June Paik used video to challenge conventional narratives and aesthetics, often incorporating performance, feedback systems, and temporal manipulation into their work. As a “time-based” medium, video allowed creators to loop, stretch, compress, and destabilise linear time—qualities that suited the conceptual and performative aims of the postwar avant-garde (Meigh-Andrews, 2006; Rush, 2003).

Though initially marginalised, video art steadily gained institutional recognition throughout the 1970s and ’80s. Exhibitions such as Into the Light: The Projected Image in American Art, 1964–1977 at the Whitney Museum (Iles, 2000) and the establishment of departments for media and time-based art in major museums marked its gradual canonisation. What began as a fringe practice—screened on monitors in artist-run spaces and underground festivals—evolved into a dominant mode within contemporary art. By the 2000s, video installations occupied entire galleries, biennales, and public screens, including architectural-scale commissions such as Ryoji Ikeda’s data.scan series in Times Square.

This shift reflected broader changes in the art world, including a growing acceptance of interdisciplinary practices. Dick Higgins’ (1966) concept of “intermedia” captured the spirit of this transition, where boundaries between performance, sculpture, sound, and moving image blurred. Video art became a site of convergence for abstraction, conceptualism, minimalism, and later digital and installation art (Mondloch, 2010).

Despite its growing visibility, video art remains difficult to categorise. Much of its vocabulary is inherited from film—terms like “filming” persist even in digital contexts—and it lacks the rigid stylistic movements that define other media (Meigh-Andrews, 2006). Nonetheless, it now holds a secure place within the canon of contemporary art, studied, collected, and exhibited globally.

Shared Aesthetic and Conceptual Ground

Despite divergent contexts, VJing and video art share formal techniques and concerns. Early video art explored feedback loops, video distortion, and performativity—ideas mirrored in the VJ’s toolkit. Nam June Paik’s Video Commune (1970) involved real-time public participation in image mixing, while the Vasulkas’ Machine Vision (1978–79) processed signals live through oscilloscopes and video synthesisers (Vasulka Archive, n.d.). These analogue predecessors foreshadowed the hybrid aesthetics of VJing, where abstraction, glitch, rhythm, and remix were central. Both practices, though differently situated, question authorship, perception, and the materiality of the screen (Munster, 2006).

VJing’s exclusion from mainstream art discourse owes much to its subcultural setting and resistance to commodification. It is a performative form with no original object, created for the moment and often without lasting documentation. Its collaborative, anonymous nature and emphasis on sensory experience clashed with the art world’s preference for singular, nameable authorship, styliostic catagorisation, and stable works. Unlike the carefully curated and collectable installations of video artists, VJ sets often existed in less-than-legal parties, ephemeral festivals, or YouTube montages. Critics like Bishop (2012) and Steyerl (2009) have since challenged these hierarchies, but VJing still struggles to be fully historicised. The 2000s saw VJ aesthetics gradually enter the gallery and festival circuits. At Ars Electronica, Transmediale, and MUTEK, artists like Ryoji Ikeda, Carsten Nicolai (Alva Noto), and Nonotak Studio combined generative visuals and sound in immersive installations that mirrored VJ logic. Meanwhile, collectives like D-Fuse and AntiVJ actively bridged club and gallery worlds. Even commercial visual spectacles like United Visual Artists’ work with Massive Attack demonstrate how VJ culture reshaped expectations around live visuals (Licht, 2007). The influence of VJing is also evident in popular immersive art experiences—like teamLab and Refik Anadol—that merge spectacle with interactivity (Paul, 2016).

Conclusion

In short, VJing challenges the boundaries of what constitutes art by occupying a liminal space between entertainment, activism, and aesthetic exploration. Its marginalisation underscores the art world’s ongoing difficulty with live, networked, and collective practices. Yet its influence is undeniable. As museums embrace VR, real-time generative art, and participatory environments, VJing appears not as a peripheral activity but a pioneer of these formats. Recognising VJing within the broader lineage of media art is not merely an act of inclusion—it’s an acknowledgment that the canon itself must evolve in response to the expanded field of cultural production (Grau, 2003; Bishop, 2012).

Bibliography

Bishop, C. (2012) Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship. London: Verso.

Elsaesser, T. (2016) Film History as Media Archaeology: Tracking Digital Cinema. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Grau, O. (2003) Virtual Art: From Illusion to Immersion. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Higgins, D. (1966) ‘Intermedia’, Something Else Newsletter, 1(1), pp. 1–2.

Iles, C. (2000) Into the Light: The Projected Image in American Art, 1964–1977. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art.

Licht, A. (2007) Sound Art: Beyond Music, Between Categories. New York: Rizzoli.

Lovejoy, M. (2004) Digital Currents: Art in the Electronic Age. London: Routledge.

McFadyan, P. (n.d.) ‘livevevil – Drum n Bass Glasgow: 2000 to 2005’. Available at: https://livevevil.wordpress.com [Accessed 15 May 2025].

Meigh-Andrews, C. (2006) A History of Video Art: The Development of Form and Function. Oxford: Berg.

Mondloch, K. (2010) Screens: Viewing Media Installation Art. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Munster, A. (2006) Materializing New Media: Embodiment in Information Aesthetics. Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College Press.

Parikka, J. (2012) What is Media Archaeology? Cambridge: Polity Press.

Paul, C. (2016) Digital Art. 3rd ed. London: Thames & Hudson.

Rees, A.L. (1999) A History of Experimental Film and Video: From the Canonical Avant-Garde to Contemporary British Practice. London: BFI Publishing.

Rush, M. (2003) Video Art. London: Thames & Hudson.

Shanken, E.A. (2009) Art and Electronic Media. London: Phaidon.

Shapiro, M. (1981) ‘Portable Video and the Public Sphere’, Art Journal, 41(1), pp. 29–35.

Spinrad, P. (2005) The VJ Book: Inspirations and Practical Advice for Live Visuals Performance. San Francisco: Feral House.

Steyerl, H. (2009) ‘In Defence of the Poor Image’, e-flux journal, 10. Available at: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/10/61362/in-defense-of-the-poor-image/ [Accessed 15 May 2025].

Subvert Central. (2005) ‘LVE 5th B’day – Doc Scott (3 hr set) & VJ Anyone’ – 3rd June. Available at: https://subvertcentral.com/forum/thread-19178 [Accessed 15 May 2025].

The Vasulka Archive. (n.d.) ‘Steina and Woody Vasulka’. Available at: http://www.vasulka.org [Accessed 15 May 2025].

Youngblood, G. (1970) Expanded Cinema. New York: Dutton.

Leave a comment